#nineteen to twenty icons

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

nineteen to twenty like or reblog if you use them

#nineteen to twenty icons#nineteen to twenty#19/20#reality show#reality shows icons#netflix#jeong ji woo#jeong jiwoo#choi yerin#choi ye rin#icons#without psd

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

can we get some more background on collide’s ellie before the story started? lowkey curious about her groupie days hahaha

THANK YOU GORG NONNIE I'VE ALWAYS WANTED TO WRITE THIS. TURN IT UPPPP

Rockstar!ellie williams’ life before you came crashing into it was already wild in its own right. the fireflies started as this messy little project in high school, just three angsty teenagers skipping class to rehearse in jesse’s garage and dream too big. but from the very beginning, ellie had that thing. that frontwoman energy. raw, magnetic, loud when she wanted to be and quiet in the moments that mattered.

of course, being joel miller’s daughter didn’t hurt either. the joel miller—rock legend, guitarist god, literal music royalty. she grew up with guitars in every corner of the house, got her first custom pedal at twelve, and was getting dropped off at school in a vintage mustang with the windows down and her dad blasting nirvana like he wasn’t a whole icon. people were paying attention before she even opened her mouth.

their debut album dropped when she was barely nineteen and it exploded. like, charts on fire, critics losing their minds, fans already tattooing lyrics on their ribs kind of explosion. it was rough and loud and painfully honest, and people ate it up. suddenly the fireflies were everywhere—magazine covers, award shows, late night interviews where ellie would always roll her eyes and let dina do the talking.

and ellie? ellie was living like a rockstar. full-speed. full-chaos. she had girls lined up at every venue, backstage passes tucked into her back pocket like candy. groupies every night, different cities, different names she couldn’t remember in the morning. she wasn’t cruel about it, just detached. like she knew how to give people a night they’d remember forever, while she forgot it the second it was over.

there were stories, obviously. ellie williams didn’t just flirt with the whole sex-drugs-rock-and-roll lifestyle—she practically rebranded it.

like the time in chicago, where she went MIA a few hours before the show and no one could find her. security was panicking, dina was pacing, and jesse was one call away from having a heart attack—until ellie strolled into the venue ten minutes before set time, lipstick smudged all over her jaw, reeking of tequila and weed, with three girls trailing behind her like she was the messiah of sex. she still performed like nothing happened, of course. even signed a bra on stage mid-song.

or berlin, when she stopped the show halfway through, locked eyes with a girl in the front row who looked like she’d been crying, and straight-up jumped off stage. mic still in hand, she kissed her so hard it made at least 20 headlines. she never got her name, but later admitted in an interview that it was one of the best kisses of her life.

and then there was that rooftop in LA—the infamous afterparty for some alt girlband’s tour finale. ellie was already drunk, half in her underwear, making out with the rival band’s lead singer against a glass wall while their drummer tried to politely look away. jesse swears he walked in on her mid-threesome in the guest bedroom later that night, but ellie still denies it to this day. kinda.

there was one show—vegas, obviously—where ellie walked off stage with nearly twenty bras and at least ten pairs of panties stuffed into her mic stand, draped over her guitar, even hanging off her boot somehow. halfway through the set, it basically turned into a lingerie rainstorm. she played through it like a pro, flashing that smug little grin every time another piece hit the stage, only pausing once to pick up a red lace thong, twirl it around her finger, and go, “if you want it back, you’re gonna have to come get it yourself.” the crowd lost it.

dina joked that they could open a lingerie store with all the stuff ellie got that night. ellie just shrugged, grinning, and said, “what can i say? i’m a woman of the people.”

it was a mess, but it was her mess. untouchable, unstoppable, with this cocky grin and a body count that would make most people faint. music was her religion and girls were her favorite sin.

but all of that changed when you showed up. not right away—ellie was too stubborn for that. but eventually, the chaos started to feel a little quieter. the noise started to mean something. and for the first time, ellie started thinking less about the next city, and more about who she wanted waiting for her when the lights went down.

#⭒࿐COLLIDE - series#lesbian#lesbian pride#ellie williams tlou#ellie williams#ellie williams imagine#ellie williams smut#lesbian shot#ellie x reader#ellie williams x you#sapphic smut#ellie the last of us#tlou part 2#ellie tlou#ellie x fem reader#ellie x you#ellie x y/n#ellie williams x reader#the last of us 2#lesbianism#sapphic#wlw post#wlw#wlw yearning#ellie williams headcanons#ellie williams fanfiction#ellie williams the last of us#ellie willams x reader#dina woodward

332 notes

·

View notes

Text

He Walks: Dick Grayson, the Survivor

This is a meta written for the ten year celebration of Grayson. For @grayson10yearslater.

From it’s prologue in Nightwing #30, Grayson by Tom King and Tim Seeley, boldly poses its readers with the question of how to describe one of DC’s oldest and most iconic characters when he is stripped of his familiar superhero identities. Who is Dick Grayson when he can’t hide behind Robin? Nightwing? Batman?

[King, Tom; Seeley, Tim; Tynion IV, James, writers. Janin, Mikel; Hetrick, Meghan; Garron, Javier; Lucas Jorge, illustrators. Setting Son. Nightwing. 30, e-book ed. DC Comics, 2014. Page 30]

Divided into twenty issues and three annuals, the story explores the theme of identity from all angles, pushing Dick away from his comforts to dissect the different layers of his character. A hero, the end of the last issue seems to say, is the true answer to this difficult question.

[King, Tom; Seeley, Tim, writers. Antonio, Roge, illustrator. Spiral’s End. Grayson. 20, e-book ed. DC Comics, 2016. Page 23]

And while that is undoubtedly true, each of the preceding nineteen issues elaborate on what traits can folded into a hero.

Dick is a storytelling, the first annual says;

[King, Tom; Seeley, Tim, writers. Mooney, Stephen, illustrator. A Story of Giants Big and Small. Grayson. Annual 01, e-book ed. DC Comics, 2014. Page 11]

Dick is compassionate, the finale of Act I with the Paragon Brain proves;

[King, Tom; Seeley, Tim, writers. Mooney, Stephen, illustrator. Sin by Silence. Grayson. 07, e-book ed. DC Comics, 2014. Page 19]

Dick is a partner.

[King, Tom; Seeley, Tim, writers. Janin, Mikel, illustrator. Nemesis Part Two. Grayson. 10, e-book ed. DC Comics, 2014. Pages 23 to 24]

I want to focus a little bit on that last one. Dick, after all, was created to be the perfect partner. In 1940, he was the sensational character find that became Batman’s other half, the missing element to his mythos. Move further along his history, and a diverse number of writers were compelled to team Dick with other characters — he’s the Titans’ leader, the missing third piece of the World’s Finest, Batgirl’s love interest.

Grayson, too, is interested in exploring this aspect of Dick Grayson. In its first act, it pairs him up with Helena Bertinelli, whose more experience, tragic background, and darker personality is meant to mirror Batman.

Tom King: For me, it seems to make so much sense because basically she almost has that Batman female origin. She shares that origin that Batman and Dick have of having gone through this violent period when she was young and coming out of that a hero. We wanted to play with that. We wanted to play with the dichotomy of what Barbara is in Dick's life versus what Helena is in Dick's life. Helena's much closer to what Batman is and much closer to the father figure Dick was related to, so I think that creates immediate tension and fun stuff we can play with.

[Katzman, Gregg. "Interview: Tom King & Tim Seeley Talk GRAYSON." Yahoo! News, 4 Jan. 2015. Accessed 8 Dec. 2024.]

In act two, he is paired up with Tiger King of Kandahar. In fact, there is a theme of duality and partnerships throughout Grayson, showing that this is a critical aspect of who is Dick Grayson.

The exception to this is Grayson #05.

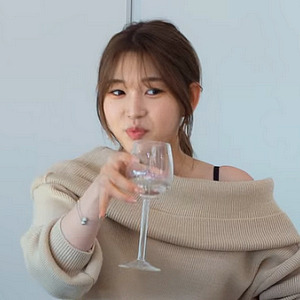

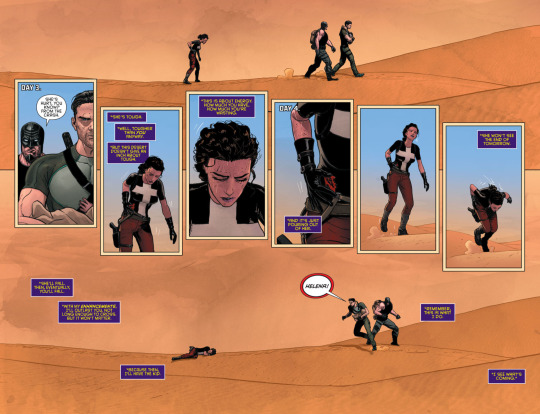

A self-contained story, Grayson #05 isolates Dick to get to the core of who he is. By contrasting Dick with Helena and Midnighter, placing him in the unforgiving vastness of an infernal desert, and calling forth the tale of Robin Dies at Dawn, Grayson #05 presents us with a man who does not give up and does not give in. Dick walks, even if he must walk, at times, alone. When laid bare, without the trappings of a superhero identity or of a partner, Dick Grayson, Grayson #05 says, is, at the core of his being, a survivor.

In this meta, I want to see just exactly how Grayson #05 does that through a close reading of the issue.

Now, without any further delay, let’s get started.

Let’s start with the cover.

[King, Tom; Seeley, Tim, writers. Janin, Mikel, illustrator. We All Die at Dawn. Grayson. 05, e-book ed. DC Comics, 2014]

Everything about this cover radiates heat. The sun is beaming down mercilessly, the spirals mimicking the sun rays, the color palette a strong orange that is highly saturated but not bright. The reader can feel how hot it is in this desert, and all around there's nothing but sand. Sand, sand everywhere the eyes can see, and in the center of the image, a lone black figure braving this infernal bare landscape.

This cover tells us not just the location of where the issue will be set, but it also shows that Dick will be alone out there. It tells us this will not be an action-filled story, but it will be one of survival. Man vs Nature, and nature does not discriminates with her ruthlessness. Dick stands alone facing the elements, but he stands. He is walking, he is not giving up. It would be so easy for this cover to have a close up of Dick's, Helena's, and Midnighter's exhausted expression as they each try to survive, but instead we just see Dick by himself, alone, walking. He does not give up, he does not give in. He survives.

The issue then opens in medias res, immediately presenting the readers with that main conflict: survival. It does not waste any time with unneeded exposition — after all, though Dick would hate this fact, we as readers do not need to know the name of the mother who is dying; we do not need to know the details of Minos’ mission before it all went wrong; we don’t even need to know how Midnighter managed to track Dick and Helena. All we need to know is that Dick and Helena, and Midnighter are all after the Paragon Heart, which belongs to the, as of this page, unborn baby; that ARGUS somehow tracked Midnighter who was fighting Dick for the Heart; and that mid-fight the mother went into labor.

There's an elegance in the way everything is conveyed so well and so quickly in this one page. It's brilliant storytelling from both a writing and a visual stand point.

[King, Tom; Seeley, Tim, writers. Janin, Mikel, illustrator. We All Die at Dawn. Grayson. 05, e-book ed. DC Comics, 2014. Page 01]

As they crash into the desert, the mother passes away. ARGUS is gone, but our trio and the newborn baby girl are faced with a mightier enemy: The desert. The nearest town is days away, they do not have a lot of supplies, they do not have how to call for help. Here, we’re faced with this issue’s main question: Can they survive this? The answer seems to be resounding “no.”

Let’s take a look at how each of the characters approach this situation.

Helena is pragmatic. She is thinking of the mission, but her expression is troubled. She doesn't see a way out of this. She knows they have to survive long enough for Spyral to eventually find them, but the odds are against them. Given the fact she’s injured, it’s unlikely she’ll ever make it out of this desert. Still, that does not mean she’ll fall into despair. She'll do what needs to be done, but she knows this is not something they can easily get out of. If she goes down, she'll go down fighting. Like I said, she’s pragmatic.

Midnighter, on the other hand, is a pessimist. He is jaded. Why bother trying? Midnighter is a nihilist. “We’re dead,” he says not once, but twice.

Then we have Dick. Beautiful Dick, he holds the baby in his arm like she's the most precious thing in the world. And in this moment, she is. His reply to Midnighter is telling. They aren’t dead. They can't be, because if they are dead, then so is she, so death is not an option. It's not a question of what is practical, of what the mission is, of what the odds are. It's not about being an optimist, either. It's simply about her. She is all that matters and she is entirely dependent on them, so they can't be dead. They cannot let her die, this little innocent child who is not even an hour old. So what will they do instead? They’ll walk. They’ll survive.

[King, Tom; Seeley, Tim, writers. Janin, Mikel, illustrator. We All Die at Dawn. Grayson. 05, e-book ed. DC Comics, 2014 Page 02-03]

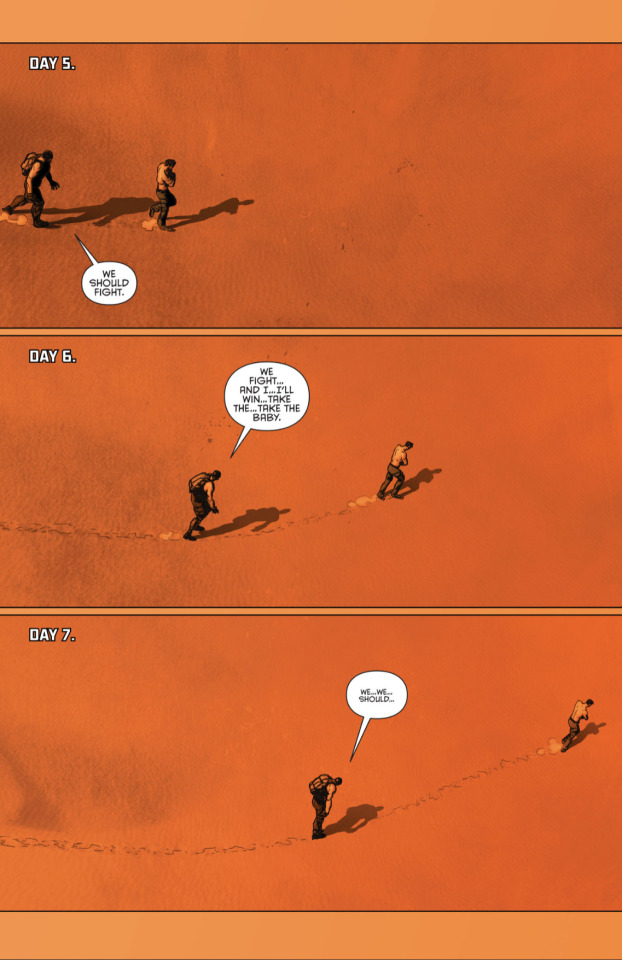

The next page displays what will become the brilliant standard for this issue — open skies, sand, and small figures walking. Everything about it conveys this vastness that is so oppressive in its openness. It's the majesty of Mother Nature.

Note how tiny the figures are. Note how Dick leads the other two, not by a little, but by a lot. In his arms Dick holds the baby, nurses her with the formula from the mother’s bag. In the pages we see Helena struggling, Midnighter drinking water and shedding away his clothes, but Dick remains stoic. He leads, separated — isolated, distant — from the rest, determined, disappearing into the far orange of the page.

In this, we see Dick’s silent determination. It’s notable that he is not trying to make light of the situation through humor. Instead, he is silent. And he walks.

[King, Tom; Seeley, Tim, writers. Janin, Mikel, illustrator. We All Die at Dawn. Grayson. 05, e-book ed. DC Comics, 2014. Pages 04-05]

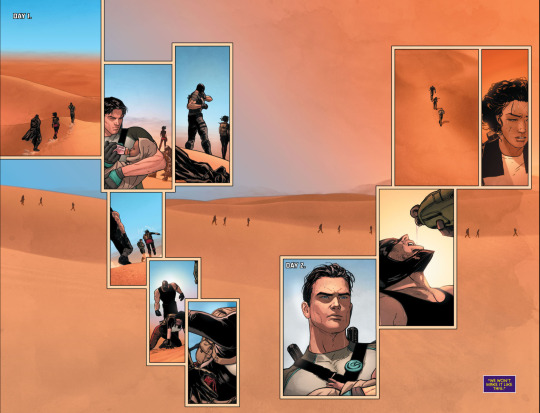

As the story continues, Midnighter’s pessimism deepens. It is notable that this issue is the first time Dick and Midnighter have seen each other since Grayson #01. And what does Midnighter do? He lashes out at Dick by revealing he knows who Dick is. This calls back to Forever Evil, where Dick’s identity was revealed to the world. Midnighter is weaponizing Dick’s trauma against him, trying to draw a reaction out of Dick. Not only that, he says that they only way to survive is to kill the baby and use the Paragon Heart. Otherwise, the odds are not in their favor, and he deems this "just walk" strategy is pointless. This is how Midnighter copes with the hopelessness of their situation — he dwells on the negative and lashes out.

Helena reacts to Midnighter by subduing the threat, but she doesn’t comment on his defeatist attitude. Nor on his plan. She is, again, practical. She won’t say they’ll make it, but she won’t allow Midnighter to pose a threat to the mission.

Dick, though… Not once does Dick acknowledge Midnighter’s taunting. Not once, not even to defend the baby. A weaker writer would have tried to get Dick to empathize with Midnighter, to tell him again that they're not dead yet, that they just need to keep trying. Instead, Dick’s refusal to even look at Midnighter shows how he won't even acknowledge the possibility of not surviving. His focus, instead, is all on her. That is what is driving him so that is what has his entire attention. Midnighter's temper tantrum is not even worth his time. Not when her survival is at stake.

I also want to take a moment to take in the environment. In this scene, the first panel shows how tiny the three of them are in the vast desert, the beautiful sky expanding above them. Mother Nature, the issue seems to say, is beautiful, worthy of awe. It is big, bigger than any human. More powerful, too. It is a challenge unlike any Dick has ever or will ever face. It cannot be charmed by him, it cannot be fought against, it cannot be conquered. It is not cruel or evil, either. It simply is, bare and uncomplicated, honest at all times. To survive her, Dick must also be the barest, least complicated version of his self.

While writing this, I often felt myself hesitating when writing about the conflict between Dick and desert. Phrases like “go against the desert,” often came to my tongue, and I had to swallow them back due to how wrong they felt. To “go against” someone (or something) is to have an antagonistic, adversarial relationship, and I’m not sure that is incredibly accurate to this scenario. The desert is indifferent towards Dick and the others. Midnighter speaks of fighting, of winning, of conquering this challenge, but Dick, by contrast, is quiet. He is not trying to “win” against the desert. That is not the right frame of mind. Rather, he is simply trying to survive.

[King, Tom; Seeley, Tim, writers. Janin, Mikel, illustrator. We All Die at Dawn. Grayson. 05, e-book ed. DC Comics, 2014. Pages 06 - 07]

As time passes, Midnighter continues to talk. To taunt. His negative attitude doesn’t light up, and he is still trying to get a reaction out of Dick. Here we see that Midnighter is perhaps not fully comfortable with his enhancements, like he doesn't see himself as fully human because of them. He resents them even as he trusts his enhancements more than he trusts his own abilities. He says he sees all outcomes and there are none where they survive this. Not as humans. Not without the Heart.

Note how Midnighter presents their situation as not about being tough, but about how much energy you have. This framing seems to reject the idea of survival — of “toughing it out” — and instead looks at their situation as one of victory and defeat — you have to have enough energy to make it out of the desert, and in doing so, you’ll be victorious.

Yet, Midnighter predicts himself to outlast Dick, but in reality, he falls before Dick does. This begs the question: Was Midnighter right? Must you defeat the desert and win against it in order to win?

Personally, I believe the story is saying “no.” This is not about victory and defeat, but about survival. And to survive, one must lay themselves bare of foolish things such as pride and ego. To survive, you must dig deeper within yourself, and find something that will allow you to not go against mother nature, but to continue walking along side her.

Dick has found his something deep within himself. That something is his compassion. Helena collapses, and Dick leaves with her his shirt, laying himself bare. Yet, despite his fallen partner, his priority is still the baby girl. He will survive for her, and in this action we see the depths of Dick’s compassion for others. He continues to walk. He continues to survive.

[King, Tom; Seeley, Tim, writers. Janin, Mikel, illustrator. We All Die at Dawn. Grayson. 05, e-book ed. DC Comics, 2014. Pages 08-10]

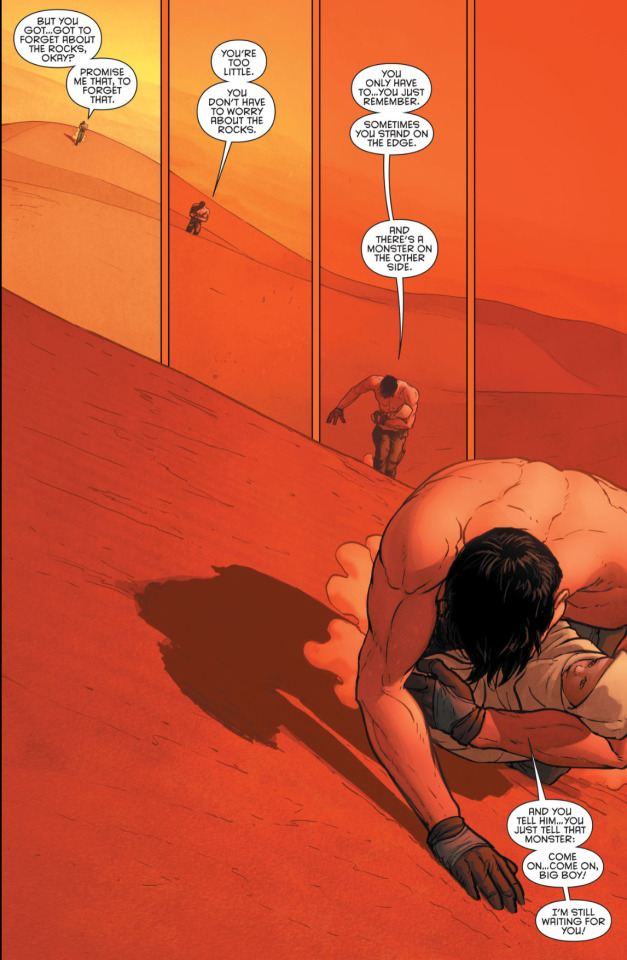

Finally, after days, Midnighter is confronted with the true force that is Dick Grayson. He was so certain he was going to outlast Dick. “I have… My… Enhancements. I have powers,” he struggles to say. But what does Dick have? How can a simple man continue to go against these conditions?

This page shows how deeply Midnighter underestimated Dick’s humanity and his compassion. Dick is not a superpowered individual, no, but Dick’s determination is unlike at other. This is who he is… Someone who walks.

Dick is a survivor. When Dick was a small boy, he lost his entire world in a traumatic act of violence. From the moment those ropes snapped and the Flying Graysons plunged to their deaths, Dick became a survivor — someone who had to figure out how to walk forward when everything seemed lost. And Dick did it.

If I can go on a bit of a tangent here, I’ll say that I really dislike whenever child heroes are characterized as child soldiers, be it by fans or by canon writers. This reading is, in my opinion, incredibly lazy and displays a lack of understanding of what superhero identities are meant to stand for. We can discuss the traumas that come along with being a child hero, but to dismiss it as a universally bad thing and equating to the real world horror of child soldiers ignores the fact that this is a fictional world in which the fantastical concepts act as metaphors for larger ideas.

Robin is not a child soldier. Robin, much like Batman, is a response to trauma. Specifically, Dick’s Robin is a response to the trauma of being a survivor of violent crime, and Robin demonstrates how a victim can regain agency and transform their tragedy into an empowering narrative. As Steve Braxi points out in his On Superman, Shootings, and the Reality of Superheroes essay, Batman “transform[s] trauma into will power,” and Dick, whose story is meant to mirror that of Bruce’s, does the exact same through Robin. Through Robin, Dick is able to not only find justice for his parents, but he is also to help other survivors like him. And that is what allows him to keep on walking.

This is what Grayson #05 demonstrates. It strips away the metaphor of the hero identities and the distraction of partnerships, laying Dick out bare and showing that as long as he can help someone, as long as he has his compassion, Dick Grayson can survive anything.

[King, Tom; Seeley, Tim, writers. Janin, Mikel, illustrator. We All Die at Dawn. Grayson. 05, e-book ed. DC Comics, 2014. Pages 12 - 13]

In the following page, the vastness of the desert is contrasted with close up shots of the baby. We see Dick, so impossibly small standing against a large desert that disappears into the horizon, and ocean of sand and oranges, and we see the whole reason why Dick is still alive. The environment that may kill him is contrasted with the reason why he will survive.

“I’m here. I’m here,” Dick tells the baby girl as she ceases her cries. “I’m still here.”

He gets up… And he walks. The repetitiveness of the action throughout the issue emphasizes the slog of the immediate aftermath of a traumatic event, those moments when you realize time is progressing forward as it always had, but your mind and heart are still stuck in that one moment that changed your life forever. All Dick can do is walk, walk, walk, yet he is still lost in this vast desert, the trauma is still overwhelming him, there’s no end in sight… But he does have his reason for not giving up — his compassion allows him to continue onward.

[King, Tom; Seeley, Tim, writers. Janin, Mikel, illustrator. We All Die at Dawn. Grayson. 05, e-book ed. DC Comics, 2014. Pages 14 - 15]

Robin Dies at Dawn is the title of Batman #156. In this two part story Batman finds himself in an alien planet filled with threats. Robin saves him from sentient, walking plants, and after escaping, they find a giant stone idol that comes to life and begins chasing them. They manage to leap over a deep fissure and realize that if the stone idol were to do the same, the unstable down would crumble and the stone idol would fall, securing their safety. As they wait for the idol, they see that it, too, realized the ground was unstable and it tries to figure out a safer passage to the other side. That’s when Robin provokes the stone idol, who, in fury, grabs a boulder to throw at Robin. Before it can do it, the floor crumbles and it falls, but boulder still hits Robin and kills him. Later, it is revealed that this was a hallucination induced by an experiment Batman subjected himself to meant to study the effects of loneliness in astronauts. Through the following days, Bruce has occasional hallucinations of alien creatures putting Dick in danger. It isn’t until Dick’s life is threatened by the Gorilla Gang that Bruce is able to “overcome” the lingering effects of the experiment, the threat to Dick’s life being enough to “shock” him back to normal.

[Finger, Bill; Boltinoff, Henry; Schiff, Jack, writers. Moldoff, Sheldon; Boltinoff, Henry, illustrators. Robin Dies at Dawn. Batman. 156, e-book ed. DC Comics, 1963. Page]

To the baby girl, Dick recounts this Golden Age story as if it were a dream, focusing on the part where the stone idol kills him with the boulder. In this tale, we go back to Robin, Dick’s first survival mechanism, and to the first person who first showed him compassion and to whom his survival was paramount — Batman.

Though so far Dick has rejected the idea of victory vs defeat, he presents the baby with a scenario where he is faced with such a conflict. Yet, in this case, to “go up against” the enemy is to call them forward so they will fall. Dick’s taunting leads the stone idol to it’s defeat, and this is the point which Dick says he wants the baby girl to focus on. You must welcome danger, he seems to say, and face it head on. You must walk forward instead of running away.

Yet, it is notable that the enemy is not the only one who is defeated in this story. After all, Dick “dies” at dawn. This is what Dick doesn’t want the baby to focus on, but I think it’s important in understanding this idea of survival. In the story, Dick sacrifices himself so Batman can escape. He goes up against an enemy, he achieves victory, but he does not survive. But, crucially important, Batman does.

This paints a picture where Dick's survival and his victory are not one and the same. Not the way Midnighter seemed to have believed. While Dick’s compassion is intrinsically tied to his status as a survivor of violence, this story seems to indicate that Dick will readily relinquish his own survival for the sake of someone else. In the framing of victories and defeats, other people’s safety -- other people's survival -- is Dick’s “win” condition.

This, I believe, demonstrates how Dick's compassion allows him to pass own his survivor status to others, even at the cost of his own life. By shielding them and giving them the opportunity to move past a trauma, Dick creates other survivors. He becomes their protector, their patron saint.

[King, Tom; Seeley, Tim, writers. Janin, Mikel, illustrator. We All Die at Dawn. Grayson. 05, e-book ed. DC Comics, 2014. Pages 16 - 18]

Dick Grayson is a lot of things, and he has numerous qualities. He is a partner, a hero, and a friend; he’s good, he’s funny, and he’s brave. While all of those are important aspects of his character, they can also distract from one characteristic that is crucial to Dick’s genesis.

Before he was Agent 37, before he was Nightwing, before he was Robin, Dick was a survivor. Having survived violence, Dick used his compassion to transform his trauma into power. Grayson #05 isolates Dick from the world, putting him in a dangerous and revealing desert to expose his ability to survive through his compassion. This, the story says, is who Dick at the core of his being, when stripped away from the distractions of partnerships and superhero metaphors. This is who Dick Grayson is: He is a man who walks.

Bibliography:

Braxi, Steve, “On Superman, Shootings, and the Reality of Superheroes” Comics Bookcase, September 2021

Finger, Bill; Boltinoff, Henry; Schiff, Jack, writers. Moldoff, Sheldon; Boltinoff, Henry, illustrators. Robin Dies at Dawn. Batman. 156, e-book ed. DC Comics, 1963

Katzman, Gregg. "Interview: Tom King & Tim Seeley Talk GRAYSON." Yahoo! News, 4 Jan. 2015. Accessed 8 Dec. 2024

King, Tom; Seeley, Tim, writers. Janin, Mikel, illustrator. We All Die at Dawn. Grayson. 05, e-book ed. DC Comics, 2014

King, Tom; Seeley, Tim, writers. Mooney, Stephen, illustrator. A Story of Giants Big and Small. Grayson. Annual 01, e-book ed. DC Comics, 2014

King, Tom; Seeley, Tim, writers. Mooney, Stephen, illustrator. Sin by Silence. Grayson. 07, e-book ed. DC Comics, 2014

King, Tom; Seeley, Tim, writers. Janin, Mikel, illustrator. Nemesis Part Two. Grayson. 10, e-book ed. DC Comics, 2014

King, Tom; Seeley, Tim, writers. Antonio, Roge, illustrator. Spiral’s End. Grayson. 20, e-book ed. DC Comics, 2016

King, Tom; Seeley, Tim; Tynion IV, James, writers. Janin, Mikel; Hetrick, Meghan; Garron, Javier; Lucas Jorge, illustrators. Setting Son. Nightwing. 30, e-book ed. DC Comics, 2014

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

LAYLA MULLIS ✶ 𝓑𝗘𝗧𝗧𝗘𝗥 𝗖𝗥

﹙🧸ྀི﹚ LAYLA LOTTIE MULLIS is the internet's favorite amateur filmmaker, sarcastic internet commentator, and deadpan podcast host. she is known for her youtube interview show, the b8ll﹙the eight ball﹚, where she hosts many of the twenty-first century’s heart throbs, rappers, and internet personalities.

﹙📌﹚ two thousand twenty-five // cincinnati, ohio

layla was born november fifteenth, two thousand and six in northern ohio. her first glimpse at fame was in two thousand and nineteen when a viral tweet led to her gaining eleven thousand followers in one night. she would then begin her youtube career as a freshman in high school. back then her content was a variety of vlogs and baking challenges with her friends. today her content had transitioned into video essays and discussions on history. she also started her youtube talk show the b8ll in the fall of two thousand and twenty-four. the talk show has been a resounding success, acting the attention of fans who want to know more about their favorite icons.

﹙ᥫ᭡﹚ college basketball!jason todd ﹙best friends to lovers / soulmates﹚

layla and her long-term boyfriend, jason, met way back in the fourth grade when she moved to his city. the two bonded over fidget spinners, a staple of two thousand and sixteen. layla recalls he had an awful shaggy haircut and always wore a pair of awful cargo shorts. jason recalls her wearing her long hair in a terrible ponytail every day. but looking back at the pictures of them during the last day of fourth grade the duo is quite adorable. in said photo, they were both wearing white t-shirts with their friends and classsmates' colorful signatures all over them. she does not remember the first impression she had of him, but she does remember the first time she knew she was crushing. she retells a story of recess in the fifth grade and him picking her first for kickball. it was the first time she was enamored with him. and only six years later, the two would get together.

#shiftblr#shifting#shifting blog#reality shifting#shifting realities#jason todd#jason todd x reader#jason todd x you#© laylasverse .#betterreality.com#reality ꫂ᭪ introduction

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

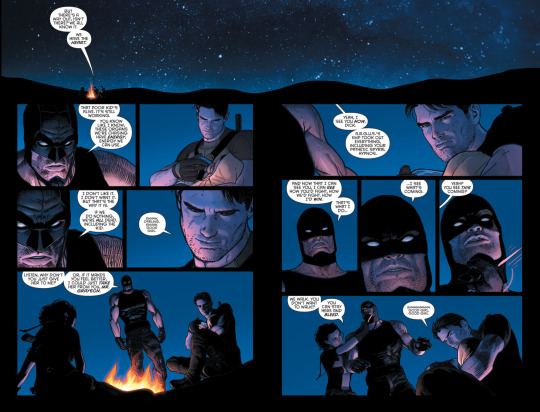

writer x matt boards 🐇🩰🦢🎀🍂🪵🌑🎮

redhead, nineteen, law student, bookworm, loves pink and bows, ballet dancer, collects jellycats, fall lover, sambas enthusiast, hopeless romantic, gracie abrams girl, atwtmvftv, lip gloss, shopaholic, introvert, canadian.

brunette, twenty-one, youtuber, reads sometimes, loves blue, fall lover, likes jellycats, video game enthusiast, introvert, fashion icon, mental health advocate, clairo fan, tattooed, american.

a/n: maybe one day i’ll do a face reveal, but for now you’ll have to use this as reference!

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Beautiful Story of Life

Shared with me by a friend.

The first day of school our professor introduced himself and challenged us to get to know someone we didn’t already know.

I stood up to look around when a gentle hand touched my shoulder. I turned round to find a wrinkled, little old lady beaming up at me

with a smile that lit up her entire being.

She said, “Hi handsome. My name is Rose. I’m eighty-seven years old. Can I give you a hug?”

I laughed and enthusiastically responded, “Of course you may!” and she gave me a giant squeeze.

“Why are you in college at such a young, innocent age?” I asked.

She jokingly replied, “I’m here to meet a rich husband, get married, and have a couple of kids…”

“No seriously,” I asked. I was curious what may have motivated her to be taking on this challenge at her age.

“I always dreamed of having a college education and now I’m getting one!” she told me.

After class we walked to the student union building and shared a chocolate milkshake. We became instant friends. Every day for the

next three months, we would leave class together and talk nonstop. I was always mesmerized listening to this “time machine” as she shared her wisdom and experience with me.

Over the course of the year, Rose became a campus icon and she easily made friends wherever she went. She loved to dress up and she reveled in the attention bestowed upon her from the other students. She was living it up.

At the end of the semester we invited Rose to speak at our football banquet. I’ll never forget what she taught us.

She was introduced and stepped up to the podium. As she began to deliver her prepared speech, she dropped her three by five cards on the floor. Frustrated and a little embarrassed she leaned into the microphone and simply said, “I’m sorry I’m so jittery. I gave up beer for Lent and this whiskey is killing me! I’ll never get my speech back in order so let me just tell you what I know.”

As we laughed she cleared her throat and began, “We do not stop playing because we are old; we grow old because we stop playing.

There are only four secrets to staying young, being happy, and achieving success. You have to laugh and find humor every day. You’ve got to have a dream. When you lose your dreams, you die. We have so many people walking around who are dead and don’t even know it!There is a huge difference between growing older and growing up.

If you are nineteen years old and lie in bed for one full year and don’t do one productive thing, you will turn twenty years old.

If I am eighty-seven years old and stay in bed for a year and never do anything I will turn eighty-eight.

Anybody can grow older. That doesn’t take any talent or ability. The idea is to grow up by always finding opportunity in change.

Have no regrets.

The elderly usually don’t have regrets for what we did, but rather for things we did not do. The only people who fear death are those with regrets.”

She concluded her speech by courageously singing “The Rose.”

She challenged each of us to study the lyrics and live them out in our daily lives.

At the year’s end Rose finished the college degree she had begun all those years ago. One week after graduation Rose died peacefully in her sleep.

Over two thousand college students attended her funeral in tribute to the wonderful woman who taught by example that it’s never too late to be all you can possibly be.

These words have been passed along in loving memory of ROSE.

REMEMBER, GROWING OLDER IS MANDATORY. GROWING UP IS OPTIONAL.

“We make a Living by what we get, We make a Life by what we give.”

203 notes

·

View notes

Text

source - https://twitter.com/CalltoActivism

I absolutely love this story…….. It made me cry.

"An 87 Year Old College Student Named Rose The first day of school our professor introduced himself and challenged us to get to know someone we didn’t already know.

I stood up to look around when a gentle hand touched my shoulder. I turned round to find a wrinkled, little old lady beaming up at me with a smile that lit up her entire being.

She said, “Hi handsome. My name is Rose. I’m eighty-seven years old. Can I give you a hug?”

I laughed and enthusiastically responded, “Of course you may!” and she gave me a giant squeeze. “Why are you in college at such a young, innocent age?” I asked.

She jokingly replied, “I’m here to meet a rich husband, get married, and have a couple of kids…”

“No seriously,” I asked. I was curious what may have motivated her to be taking on this challenge at her age.

“I always dreamed of having a college education and now I’m getting one!” she told me. After class we walked to the student union building and shared a chocolate milkshake.

We became instant friends. Every day for the next three months, we would leave class together and talk nonstop. I was always mesmerized listening to this “time machine” as she shared her wisdom and experience with me.

Over the course of the year, Rose became a campus icon and she easily made friends wherever she went. She loved to dress up and she reveled in the attention bestowed upon her from the other students. She was living it up.

At the end of the semester we invited Rose to speak at our football banquet. I’ll never forget what she taught us.

She was introduced and stepped up to the podium. As she began to deliver her prepared speech, she dropped her three by five cards on the floor. Frustrated and a little embarrassed she leaned into the microphone and simply said, “I’m sorry I’m so jittery. I gave up beer for Lent and this whiskey is killing me! I’ll never get my speech back in order so let me just tell you what I know.”

As we laughed she cleared her throat and began, “We do not stop playing because we are old; we grow old because we stop playing. There are only four secrets to staying young, being happy, and achieving success.

1) You have to laugh and find humor every day.

2) You’ve got to have a dream. When you lose your dreams, you die.

We have so many people walking around who are dead and don’t even know it!

3) There is a huge difference between growing older and growing up.

If you are nineteen years old and lie in bed for one full year and don’t do one productive thing, you will turn twenty years old.

If I am eighty-seven years old and stay in bed for a year and never do anything I will turn eighty-eight.

Anybody can grow older.

That doesn’t take any talent or ability.

The idea is to grow up by always finding opportunity in change.

4) Have no regrets.

The elderly usually don’t have regrets for what we did, but rather for things we did not do. The only people who fear death are those with regrets.”

She concluded her speech by courageously singing “The Rose.

She challenged each of us to study the lyrics and live them out in our daily lives. At the year’s end Rose finished the college degree she had begun all those years ago. One week after graduation Rose died peacefully in her sleep.

Over two thousand college students attended her funeral in tribute to the wonderful woman who taught by example that it’s never too late to be all you can possibly be.

When you finish reading this, please send this peaceful word of advice to your friends and family, they’ll really enjoy it!

These words have been passed along in loving memory of ROSE.

REMEMBER, GROWING OLDER IS MANDATORY. GROWING UP IS OPTIONAL.

We make a Living by what we get,

273 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nissa Revane, William Wordsworth, and Me

Introduction:

We are not isolated individuals but an interconnected web. Part of embracing green's philosophy is understanding the importance of how each of us figures into the lives of the others. Grasping the role this larger group plays is a vital piece in understanding how the world works. - Mark Rosewater: “It’s Not Easy Being Green Revisited” … Therefore am I still A lover of the meadows and the woods And mountains; and of all that we behold From this green earth; of all the mighty world Of eye, and ear,—both what they half create, And what perceive; well pleased to recognise In nature and the language of the sense The anchor of my purest thoughts, the nurse, The guide, the guardian of my heart, and soul Of all my moral being. - William Wordsworth: “Tintern Abbey” How wonderful there should be a thing we don't yet know. - Magic Creative Team: “Renewal”

What do Nissa Revane, elf animist who had a good run in the 2010's as Magic’s iconic green planeswalker, William Wordsworth, nineteenth century British poet and the godfather of English Romanticism, and I, a mentally ill librarian who spends all his free time playing a children’s card game, all have in common? Not much, really. I’m neither a lesbian that wields earth-shaking magic nor am I the founder of a poetic movement that English majors still fawn over. However, thankfully for me, the human experience transcends time, gender, sexual preference, and even reality. There’s a lot to learn from both fiction and poetry, and I’m nothing if not a curious student. In particular, though, I’d like to talk about transitions.

The past couple of years for me have been packed full of constant transitions: I had an emergency move away from the city I had built a life in, I finished a master’s degree in library science, and I began the long, arduous process of changing careers. Not every transition has been so traumatic, though, as I am also now in a joyful, peaceful relationship and have finally achieved a modicum of financial stability on my own terms.

Needless to say, these transitions have had me feeling introspective (even more so than usual), and I have found myself seriously wondering about my place in the world. That probably sounds dramatic (well, if the shoe fits), but as an elder millennial who was around to witness when the first acorn fell from the first tree and the first scene boy put on girl jeans to pair with his trucker’s hat, I honestly just kind of gave up on that brand of stability at some point; after all, I was fifteen on 9/11, nineteen and living in Louisiana when Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans and washed away whatever trust I had left in our institutions, and twenty-one when the Bush-era recession nailed my post-undergrad job prospects into a coffin. Of course, at the risk of sounding like I’m trying to appeal to your sense of pity, I’ll admit that today’s generation coming of age during Trump and and Covid have probably had it worse than I did and have also proven themselves much stronger and more resilient than I ever was, but nevertheless, a swirling concoction of circumstances and terrible mental health habits left me feeling for decades that I’d never have a place in the world to call many own.

All that said, in my attempt to carve out a life for myself and discover my role within my larger community, I started rereading Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Keats (the poets of English Romanticism were my favorite discovery as a literature student and some of the only writers I have carried with me beyond academia), since their poetry also dealt in themes of self-discovery, memory, and transition (also, their poetry is broody and navel-gazing - something I definitely relate with). However, as a Magic: The Gathering Vorthos with basic forest brainrot, I was also struck on this reread just how close my own experiences and the themes of the Romantic Poets mirrored how my favorite green characters from Magic fiction navigate their world. At first, I felt that this is fairly low-hanging fruit, since on the surface, themes like “finding yourself in nature,” “the rejection of social norms,” “celebrating your connections,” etc. are common enough to be found in all sorts of literature. However, the more I thought about it and connected the dots in my head, the more I realized just how much green’s themes in modern Magic fiction, particularly as expressed through Nissa Revane, helped me understand my own place in the world.

Indeed, while this essay grew out of the concept of tracing the similarities between Green Magic and Romantic Poetry (not the most riveting read for most of you, I’m sure), this particular tale kind of grew in the telling (to loot a phrase from Tolkien) until it became my own personal journal of self-discovery. If the entire m.o. of my online presence didn’t already give it away, my love of Nissa Revane - planeswalker, animist, green mage, icon - colors most of my thoughts about Magic: The Gathering, and this is no different. Compiling Nissa’s arc throughout Magic’s Story, synthesizing it with the things I love the most about the Romantic poets, and letting it stew around in my brain for the last year highlighted something of vital importance to me: the message, one that weaves its way throughout Nissa’s entire narrative, that personal growth means learning that the definitions I have held onto for my whole life - of myself, of other people, of even nature and the universe itself - are but a narrow, small part of a greater whole; that embracing healthy connection with the world around me and seeking to understand my place within it helped change parts of me that I thought were intrinsic to my very nature and helped me bloom into the best version of myself.

Part I:

(me, trying to juggle graduate school and work)

Last year around this time, I found myself struggling. I was wrapping up my last full semester of my graduate program, failing miserably at balancing school and work, isolating myself from my friends because of how busy I was, and unhappy about living in Central Texas again after I swore I was done with the region. Throughout all of this, following Magic Story was a boon to my shocked nerves, though I rarely found time to follow it completely. It wasn’t pure joy, however, because as a result of stress mixed with the, at the time, untreated depression and anxiety, Nissa getting compleated - with “no way” of getting healed - during the “All Will Be One” story (not to mention that her tragic loss happened OFF SCREEN - the disrespect) severely bummed me out, so I tuned most the “March of the Machine” stories out to focus on wrapping up my semester. That is, I tuned it out until the final story, K. Arsenault Rivera’s “Rhythms of Life” was released in late March. Letting Chandra and a healed Nissa kiss at the end was a nice touch, but it was not for another month until we found out what happened to them after the climax of the Phyrexian stories.

When that month passed, however, on May 1, Grace P. Fong’s “She Who Breaks the World,” was released in tandem with previews for “March of the Machine: The Aftermath” products. Of course, I was going to like this story because I like Nissa and Chandra, and I have been a proponent of them being romantically involved since “Zendikar Resurgent,” but this story struck a deeper chord in me than I expected. I felt an immediate kinship with Fong’s representation of Nissa, a character who is also in a state of transition: in a place she doesn’t want to be, isolated from her friends and loved ones, and trying to redefine who she was after traumatic events left her floating listlessly throughout her world.

The events of “All Will be One” and “March of the Machine,” after all, were Nissa’s darkest hours in a life full of dark hours. Her mind enslaved and her bodily autonomy stolen from her, Nissa was forced to do things in service to the Phyrexian matriarch Elesh Norn that horrified her. However, due to the nature of Phyrexian compleation — having her mind and body altered on a genetic level — she performed these actions in the moment with fanatical zeal, even pleasure. We are told in the first episode of the March of the Machine arc, “Triumph of the Fleshless” that Nissa “is the finest gift the Planeswalkers have given Phyrexia. Even standing at Norn's side, she can steer Realmbreaker's attention. To say nothing of her combat capabilities. If things continued at this rate she might overtake Tamiyo as Norn's favorite new servant.” Later on in “She Who Breaks the World,” while Nissa is reflecting on this, she notes that the alterations the Phyrexians made to her “granted her the ability to unleash a call through the branches of the Invasion Tree and speak the glory of Phyrexia to every plane in the Multiverse. And right now, Nissa is disgusted with herself because—despite her friends' sacrifices, despite Chandra's sacrifices—part of her misses hearing those planes.”

On the other side of these events, Nissa is mostly healed from what the Phyrexians did to her (outside of a metal cage imprisoning her chest and some scarring on her limbs where metal was grafted on), her mind is returned to her own control, and she and Chandra are finally sharing mutual love and affection instead of being mired in “will they/won’t they” hell like they had been for nearly a decade of Magic Story. However, the trauma of knowing, remembering, and feeling intimately all of the terrible things she did understandably leaves her feeling like an outcast among loved ones, and to make matters worse, she is now with a planeswalker spark, meaning she got depowered significantly and can no longer go back to her beloved Zendikar, her homeworld that she has a close intimate connection with. All this is to point out that Nissa finds herself in a spot where she has to completely redefine who she is. Nissa took great pride in being animist; now, she cannot hear the voice of the planes and her magic is basically useless. Nissa had previously discovered meaning for herself being a member of the Gatewatch: traveling the planes doing good where can and making connections with new worlds and interesting people; now, she is trapped on a plane that does not listen to her among people she very directly harmed when her mind and body were not her own.

After a failed attempt to connect with the world of Zhalfir, Nissa begins to despair, believing that the planes have rejected her because all of the social connections she has made over the years. Nissa believes that “[s]he has spent so long connected to others that she has smothered her own connection to the Multiverse. Whether or not those bonds were made of her own volition, the planes have rejected her.” While she recognizes deep down, even if she can’t forgive herself for it just yet, that what happened while she was a Phyrexian wasn’t her fault, Nissa comes to believe that her original sin that led to this was in getting involved with the wider universe in the first place. She (and everybody who suffered from her actions as a Phyrexian) would be better off, she believes, if she had remained in her primordial, untarnished state of a champion of nature.

At this point in the narrative, Nissa’s experience reflects the way poets and writers of the Romantic Period mythologize their own world. Canadian literary critic and theorist Northrop Frye (a theorist who, truth be told, I disagree with in many respects, though his work on the Romantic Period is exhaustive and insightful) called this the “Romantic Myth.” In “A Study of English Romanticism,” Frye describes how the Romantic Myth delineates from traditional mythology:

In the older mythology the myth of creation is followed by a gigantic cyclical myth, outlined in the Bible, which begins with the fall of man, is followed by a symbolic vision of human history, under the names of Adam and Israel, and ends with the redemption of Adam and Israel by Christ. The two poles are the alienation myth of fall, the separation of man from God by sin, and the reconciling, identifying, or atoning myth of redemption which restores to man his forfeited inheritance. Translated into Romantic terms, this myth assumes a quite different shape. What corresponds to the older myth of an unfallen state, or lost paradise of Eden, is now a sense of an original identity between the individual man and nature which has been lost.

Ignoring, for a moment, the gender essentialism Frye uses, note how the lost Eden of the Romantic period was connection to nature itself. Joining society, spending precious hours having “dialogues of business, love, or strife” - all of these things are the sins that tear us away from our original, perfect self. William Wordsworth begins his “Ode: Intimations of Immortality” this way:

There was a time when meadow, grove, and stream, The earth, and every common sight, To me did seem Apparelled in celestial light, The glory and the freshness of a dream. It is not now as it hath been of yore;— Turn wheresoe'er I may, By night or day. The things which I have seen I now can see no more.

To the persona of Wordsworth’s poem, this sense of identity was lost in childhood; in Nissa’s head, she “smothered her own connection to the Multiverse” when she started to value her connections to other people — Chandra, the rest of the Gatewatch, Yahenni, and many others she let into her life — at the expense, apparently, of the natural world. What’s left for her except to turn back to nature and attempt to find herself again?

Part II:

(Nissa's oath to protect the life of "every plane" plays a huge role in her identity)

What does “finding herself” look like for Nissa, though? To answer that, let’s look at a few different things. Here, we’ll examine Nissa’s place as a green character in Magic’s color pie and pick apart the ludonarrative elements in Nissa’s card designs that informs how she approaches her idea of self.

Nissa is the only planeswalker of the original five Gatewatch to have cards that branch out to other colors. At heart, though, she is a green character. Even though she has some blue elements in her personality (curiosity) and black (the ambition to make her ideals reality, whatever the cost), Nissa’s heart is “green to the very door.”

In his near ten year old article, Mark Rosewater writes this about the philosophy of Green:

The natural order is a thing of beauty and has all the answers to life's problems. The key is learning to sit back and recognize what is right in front of you. Each individual is born with all the potential they need. The secret to a happy life is to recognize the role you were born into and then embrace it. Do what you were destined to do. The world is this elaborate system, and each one of us gets to play a part. And it's not something we have to guess about; it's imprinted on us, it's in our genes. Just look within.

It’s very easy to see Nissa in the first paragraph: even though she is a warrior out of necessity, she too craves peace and acceptance and this is revealed in one of her favorite hobbies: meditating. Nissa’s animist powers (more on that here) let her reach her consciousness into nature itself so that she can just exist among the wonders of life. Take note of this gorgeous passage near the end of “Renewal,” the last story of the Kaladesh block:

There were rivers in the air; they carried her like a mote of pollen. Great hearts were pounding in the deeps of the sky, singing slow symphonies of joy. Wordless, they expressed the sun breaking over the edge of clouds; the sharpness of stars over frosted peaks; the awareness of a new life growing within, nestled and patient, waiting for its first breath of radiance. She drifted bodiless among the singers, listening. Back and forth they called, echoing across cloud and current, composing shared dreams of weightlessness, rain, and memory. An eye the size of a house blinked. Radiant curiosity washed over her, like the return of sunlight from beyond the edge of all things. There is something new in our sky, it sang in language of sensation and vibrance; quickened heartbeats and quivering muscle; caught breath and a hundred shades of blue. How wonderful there should be a thing we don't yet know.

Nissa is an expert at recognizing “what is right in front of you,” though due to her connection to nature, “right in front of you” could mean just about anywhere on the plane itself.

To cycle back to Rosewater’s statement, however, it’s important to take consideration of the fact that a green character does not just treat the wonders of the natural world as a conduit for inner peace, they also believe that the “secret to a happy life is to recognize the role you were born into and then embrace it. Do what you were destined to do.” What does Nissa believe the role she was born into is? What drives her throughout much of Magic’s narrative?

To put it simply, Nissa believes that she is the champion of nature itself, the chosen one of Zendikar’s worldsoul. Whenever she planeswalks to a new world, she adopts the worldsoul of the plane as her own; the first thing she usually does when touching down on new earth is to attempt to connect with the soul of the plane. Throughout whichever story arc she takes part in, she usually comes to see herself as the voice of that particular world and acts as its champion as well.

Let’s take a look at the second Innistrad block, for example. Even though her role in this story is quite small, this template still applies. Jace, after unraveling the mystery of what was happening on Innistrad, goes back to Zendikar to fetch the rest of the Gatewatch to help stop the rise of Emrakul. As she planeswalks to the battlefield, the “hill rumbled slightly, the only herald of Nissa's arrival. She frowned as she knelt down, placing her palm against the ground. ‘The mana here is dark. Twisted. It's in the soil, the trees...Emrakul did some of this, but’…‘This is your first time to Innistrad, right? “Dark and twisted” is kind of a regular feature,’ Jace continued.”

Presumably at some point later on in the story, on the flavor text on the card Splendid Reclamation, Nissa says “No matter how much a plane has suffered, there is a way to restore it." Of course, this line appears nowhere in the story, but there has always been a conflict between what has been written in Magic fiction versus what is printed on the cards. Furthermore, it’s possible that this card was a bottom-up design with the mechanics designed first and Nissa pasted on later since there wasn’t another “green character who cares about lands” present during the battle against Emrakul. Either way, Nissa comes across as a character who sees herself as the champion of nature.

Nearly all other stories Nissa takes part in give her a similar arc. In "Amonkhet," she is the first to identify just how sick and distorted the world had become under Bolas’s influence, and after a trial with the ibis god Kefnet, she ends up believing that she set herself up as a rival to Bolas, able to manipulate the leylines and the gods attached to them just as efficiently as the dragon. During :War of the Spark," in a move that would earn her the disgust of the Selesnya guild, she animates Vito-Ghazi, the home of Ravnica’s worldsoul Mat'Selesnya, in order to fight against Bolas and the zombified gods. In "Zendikar Rising," Nissa’s journey takes front and center, with her conflict with Nahiri ending with Nissa as the one true savior and liberator of Zendikar. Her brief stint during the "Brothers' War" side stories end with Nissa swearing an oath to Gaea, the worldsoul of Dominaria, to personally destroy the Phyrexians herself, no matter the cost.

Even while she was a Phyrexian during “All Will Be One” and “March of the Machine” and her mind not her own, Nissa follows a similar arc, though a twisted variation: after her capture and transformation, Nissa becomes the voice of Phyrexia, as the card All Will Be One showcases, proclaiming the plane’s glory and, through manipulating Realmbreaker (likely the single largest and most powerful living thing in existence at the time), sending “Phyrexian perfection coursing across the Multiverse.”

You can certainly see Nissa’s confidence in her station as the champion of worldsouls multiverse-wide in her cards: “Nissa, Voice of Zendikar,” “Nissa, Who Shakes the World,” “Nissa, Ascended Animist,” etc. All of these designs showcase Nissa’s might as a master of land magic. Loyalty abilities on these cards almost always animate a land into a creature that can then fight alongside her. The most powerful variation of this ability was on “Nissa, Who Shakes the World”:

On a narrative level, however, what these abilities showcase is that Nissa during this era saw herself as less a friend to nature than a master of it.

Fast forward to the aftermath of the Phyrexian invasion and Nissa is in a much different place mentally, emotionally, and even physically. As Nissa struggles to (literally) bury the physical remnants of what the Phyrexians did to her body, she feels an immense sense of loss that stems from more than just guilt. Fong describes it this way:

[Nissa] felt cut off, lost in the Multiverse with no voice calling her home. Maybe no plane would hear her ever again. They'd all lost their sparks, but only Nissa still wanted to planeswalk. Even if her friends seemed to be moving on without her, she still cared about their happiness. So not wanting to bring down the spirits of their celebration, she excused herself.

I recall seeing a few half-hearted takes on social media after this story was released expressing frustration that Nissa spent so much time in this narrative grappling with the harm that was done to her rather than acknowledging guilt for the harm she inadvertently did to others. First of all, she clearly does feel guilt for the harm Norn wrought through her:

[Her] copper skeleton is covered in mangled spikes, and those spikes are covered in the dried blood of her friends. She rubs one, and dark residue flakes off on her fingertips. She wonders whose blood it was. Maybe Koth? Maybe Wrenn? Maybe Chandra? Chandra. She had hurt Chandra, almost killed her.

Secondly, exploring Nissa as a green character shows us that Nissa has lived her life believing firmly that she was alive for a purpose: to be the voice of nature and act as its most ardent champion. However, now worldsouls won’t speak to her and her magic barely works at all. Her spirituality that drives her and her magical might that allows her to act in service of that spirituality have been unceremoniously ripped away from her. Everything Nissa has ever believed about herself has come dramatically (and traumatically) crashing down.

Nissa is a character whose entire system of beliefs has now been obliterated by her experiences, and as mentioned in the previous sections, she believes it was because her original mistake was in seeking her identity in her relationships with people rather than with her relationship with nature.

I asked at the end of part one, what’s left for Nissa except to turn back to nature and attempt to find herself again? Perhaps, however, a more apt question to ask is what’s left for Nissa at all? Yes, she and Chandra are (mostly) on the same page about their feelings for one another and yes, she is alive and physically healthy (though weakened and scarred), but notice that even if Nissa despairs about what she has lost, she shows little desire to go “back” to nature. Even though she believes with absolute certainty that “the planes have rejected her,” she stays true to her duty as one of the stronger warriors left among the surviving Mirrans; when faced with decision to either explore the brand new omenpath or to help the survivors, Fong writes, “as much as Nissa loathes to abandon the portal, she knows Koth is right. As much as the war took from her, others have lost even more. They need to help first.”

Though separated by over two-hundred years and in different genres altogether, what Nissa is going through reminds me of what Wordsworth writes in “Tintern Abbey”:

I bounded o'er the mountains, by the sides Of the deep rivers, and the lonely streams, Wherever nature led: more like a man Flying from something that he dreads, than one Who sought the thing he loved. For nature then (The coarser pleasures of my boyish days And their glad animal movements all gone by) To me was all in all.—I cannot paint What then I was. The sounding cataract Haunted me like a passion: the tall rock, The mountain, and the deep and gloomy wood, Their colours and their forms, were then to me An appetite; a feeling and a love, That had no need of a remoter charm, By thought supplied, nor any interest Unborrowed from the eye.—That time is past, And all its aching joys are now no more.

You see, Wordsworth — like Nissa, like me, and probably like you at some point in your life — found himself in the late 1700’s grieving a deep sense of loss as everything he believed in came crashing down around him. Spellbound by the fervor of Revolution-era France, he lived on the continent for years and had a child with a woman he fell in love with there, but France’s tense political relations with his home country and the Revolution descending into the Reign of Terror forced him to return to Britain. Witnessing what he saw as his utopian beliefs plummet to irredeemable violence utterly broke him (on a personal note, I likely have a different view than Wordsworth on the merits of putting aristocrats to the guillotine, but that’s another essay entirely), and — like Nissa, like most of us — had to rebuild himself from the ground up.

What a relatable human story, right? As someone who is closer to forty than he is thirty, I have stumbled upon this crossroads multiple times in my life. Years ago, it involved disentangling myself from my evangelical upbringing and accepting the fact that, though my parents and (just to give them the benefit of the doubt) many of the religious adults who helped raise me had my best intentions in mind, instructing an impressionable, vulnerable, and anxious child that deep down in the center of his being he is evil and deserves eternal torment for the crime of being born was pretty fucked up. It took years of therapy, medication, and daily affirmations to finally feel good about myself. More recently, as alluded to, going through a tough breakup, wrapping up a master’s degree, and beginning the process of changing careers all within the span of roughly two years left me scrambling in my pursuit to create a new self to be a better fit for my new circumstances.

What choices did I make at this crossroads? What about Nissa or Wordsworth?

Part III:

The answer to that question is that the three of us (Nissa, Wordsworth, and I) all came to similar conclusions. This answer is two-fold, and I hope you’re not expecting some life-altering nugget of wisdom here, because — true to the heart of a green mage — the first lesson we learned is, quite simply, the art of acceptance: acceptance of the world that is, not the world that was or the future world our anxiety creates in our mind. Rosewater writes,

Green wants acceptance.

The other colors are all focused on how they'd change the world to make it better. Green is the one color that doesn't want to change the world, because green is convinced that the world already got everything right.

There is, of course, something to be said for improving your circumstances — especially if the environment around you is toxic — and the relentless ambition to mold your life into one you are happy with, but in Nissa’s case, what she needed most was to accept that she was living in a different world than was previously. Bereft of the planeswalker spark that gave her a sense of purpose and traumatized by remembering what she did when her body and mind were being puppeted by the Phyrexians, Nissa finally comes to understand and acknowledge her new place in her new world.

Early on in Fong’s “She Who Breaks the World,” Nissa attempts to connect her soul to the leylines of Zhalfir, but instead of basking in the orchestra of the planes, the music is drowned in all of the other songs that have influenced her, her tune “muffled by dozens of new, alien voices she recognizes and despises: the Eldrazi, Bolas, and finally, loudest, Phyrexia.” This leads to her belief that was discussed previously that her original sin was embracing human connection instead of remaining the voice of Zendikar’s worldsoul.

However, at the climax of the story, Nissa shares this struggle with Chandra when the two of them are trying to fight their way out of an impossible situation. A wild, out-of-control storm elemental was threatening the Mirran survivors of the Phyrexian invasion, and Nissa and Chandra were defending the populace against it. However, the two of them are not working well together, and the elemental manages to capitalize on their poor tactics and absorbs copious amounts of steam arising from a burnt baobab tree to become a colossal being whose head caresses the sky. After they get trapped in a hole with no way out, Chandra suggests a plan of attack reminiscent of the channel-fireball combo the two of them used to destroy Ulamog and Kozilek all the way back in “Oath of the Gatewatch,” and Nissa finally admits to Chandra that her magic no longer works and expresses her deep anxieties about why: “‘it's like my voice isn't my own,’” she admits. “‘Like it belongs to Phyrexia instead, like everything I've ever connected to is drowning me out.’”

Chandra, however, does not see it that way. Choosing, for once, to think before she talks (a skill she no doubt learned from her years around Nissa), eventually concludes “‘you know … you have good connections, too.’” She continues:

‘It's true—you did bad things while they had you. But everyone you've connected with over the years with the Gatewatch, we're just happy you're still here. With us.’ Chandra sets fire to a chunk of moist dirt that was about to fall on Nissa, turning it into a soft rain of ash. ‘With me.’ For the first time since she awoke in Zhalfir, Nissa smiles. Chandra, sweet Chandra, even if she doesn't realize it, has always understood and explained emotions better than Nissa ever could. Chandra continues, ‘Your connections aren't drowning your voice, Nissa. They're changing it into something new, maybe something even more powerful. Infinite voices, infinite possibilities, right?’

What Nissa needed was not to perform some kind dramatic penance or to reject society for asceticism once again but to simply accept that the world around her had changed, that she had changed. This fact is hammered home by the next section: agreeing to try connecting to Zhalfir’s worldsoul again,

Nissa closes her eyes. She retreats inward and listens for her inner voice. It's hard, much harder than before, but Chandra is dutifully helping her concentrate, blasting the falling rock away before it can reach her. Nissa is greeted by ringing deep in her ears, but she refuses to be deterred. With her connections in mind, she picks the static apart into unique melodies, the individual songs she picked up from all around the Multiverse. She arranges them, harmonizes them, and this time, when she calls to Zhalfir, her voice is amplified in chorus. She offers an apology. The plane answers. It too was cut off from everything it knew, from the connections it had made. It, too, was scarred by Phyrexia and is growing into something new. It forgives her, and Nissa can finally forgive herself. Magic floods her flesh, her blood, her bone. She hears Chandra laugh, delighted by their success.

It’s only through accepting that her life now is different from what is used to be, through confessing that her priorities had changed, through acknowledging that presence of others in her life had made her stronger, and most importantly, through forgiving herself for what’s she did when her mind wasn’t her own that Nissa is able to reconnect to the source of her magic and her joy.

Nissa learns to reinterpret her world in a new way. This can be seen in mechanical elements as well. Most of Nissa’s planeswalker cards have her manipulating lands, either by animating them into creatures to be controlled or by fetching them from the library. Nissa, Resurgent Animist, however - the first time she has been printed as a creature since the flip-walkers of 2015 - does not do any of those things. The text on this card reads:

Landfall — Whenever a land enters the battlefield under your control, add one mana of any color. Then if this is the second time this ability has resolved this turn, reveal cards from the top of your library until you reveal an Elf or Elemental card. Put that card into your hand and the rest on the bottom of your library in a random order.

The act of playing a land during the narrative of a game of Magic is the act of a planeswalker establishing a mana bond with a certain place in the multiverse. ‘Mana bond’ is a term almost never used in Magic fiction anymore, but as far as I know, it has not been retconned either. Even if not explicitly stated, there are nods to the act of creating mana bonds throughout the tie-in fiction. Look at this section from “Nissa’s Origin: Home,” for example:

As they picked their way deeper into the marshland, Nissa formed a connection with it. She saw the beauty in the moss-laden trees, felt the magic in the mists that rose up from the brackish waters, and swayed to the song of the swarms of lion flies that circled them. She never would have believed a bog had so much to offer.

In the narrative of a game, this paragraph would simply read “Nissa plays a swamp.” Explicit or not, establishing a mana bond with a particular piece of geography means that the planeswalker can, among other things, draw mana from that place no matter where in the multiverse they are. This is why, flavorfully, a player can play Ravnica shock lands alongside Tarkir fetch lands: in the narrative of a game, your planeswalker avatar has gone to these places and forged a bond with those pieces of land.

To cycle back to the card, however, instead of manipulating the land itself, having Nissa, Resurgent Animist alongside the player allows them to, firstly, hypercharge their link to the lands they play, giving the player extra mana for the act of forming connections with lands. Secondly, the player forming connections with as many lands as possible in a single turn (two in this case) allows Nissa to discover other creatures to fight alongside them. Instead of being the champion of all nature, Nissa now fights alongside nature as an ally rather than a general. This makes it all the more fitting that according to the “Aftermath Set Design” article published last year, the original name for this card during the design process was “Nissa, Friend to Nature.”

The journey Nissa goes on lets her reinterpret herself from champion to friend, but celebrating things others consider dark and reinterpreting the world in a way to showcase its beauty was close to the heart of many Romantic Poets as well. In “To Autumn,” John Keats celebrates the season of change, a season so often characterized as a time of preparation and vigilance for the coming winter. Keats writes,

Where are the songs of spring? Ay, Where are they? Think not of them, thou hast thy music too,— While barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day, And touch the stubble-plains with rosy hue; Then in a wailful choir the small gnats mourn Among the river sallows, borne aloft Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies

Keats argues that we should not characterize an entire season through the lens of humanity. Instead of pining for spring, we should live in the moment and appreciate what fall offers us. Similarly, Nissa learns to appreciate the current, sparkless season of her life with Chandra instead pining for the life that was.

Keats again argues this in “Ode to a Nightingale”; a creature poets often infuse with sadness is only that way, he argues, because of how it is interpreted:

Thou wast not born for death, immortal Bird! No hungry generations tread thee down; The voice I hear this passing night was heard In ancient days by emperor and clown: Perhaps the self-same song that found a path Through the sad heart of Ruth, when, sick for home, She stood in tears amid the alien corn

“Thou wast not born for death,” Keats writes, meaning that the nightingale is not infused with sadness by nature, but only because that’s the emotion humans have assigned to it. Nissa too learns to stop infusing her world with despair by labeling herself as powerless, damaged, and guilty, instead choosing to enjoy the moment she is in.

It is through accepting that age and experience has changed how he views the world that Wordsworth also is able to move forward. Instead of treating nature as his “all in all,” he writes,

For I have learned To look on nature, not as in the hour Of thoughtless youth; but hearing oftentimes The still sad music of humanity, Nor harsh nor grating, though of ample power To chasten and subdue.—And I have felt A presence that disturbs me with the joy Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime Of something far more deeply interfused, Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns, And the round ocean and the living air, And the blue sky, and in the mind of man

Instead of nature being the only thing in his life, nature is now simply one of the important things in his life, a feeling too that Nissa wrestles with. Instead of hearing only the song of the leylines, the worldsoul’s tune is now just one of many melodies she sings.

Acceptance is a song I too have been singing. As a staunch leftist, living in Central Texas is not particularly suited to me, and I have left here once before. Swearing never to move back, I moved away in the 2010’s for a relationship with a woman that ended up failing some years later. Financially desperate, broken emotionally, in the middle of a graduate degree, and not having anywhere else to go, I moved back to Waco to live cheaply, wrap up my online library science degree, and re-constitute my support network. It was not easy reacclimating to life here. Though I love the people I know in the area, I felt then and still feel now haunted by the ghosts of old memories, all of which had become flavored by loss. After I finished my degree in mid-2023, it did not get much better; even though I’d become ambitious and committed to looking for work elsewhere, the job market for librarians kept me here (entry-salary positions asking for five years of experience and all that). Note that for as much as change scares me, I had dared to face those fears and dared to dream only for it to come to nothing - not an uncommon story these days, I’m afraid.

Now, however, I’m working at the public library in Temple, Texas (close enough to Waco to commute) and settled myself down for the time being. Composing a new rhythm for my life has drastically helped heal the damage that almost three years of rejection, chaos, instability, depression, and anxiety wreaked on me, but that journey began, I think, with acceptance. I’m not currently where I want to end up, but despite what my anxiety and self-doubt tell me, that’s okay. I had to accept that this is where I am at in my life right now, confess that my ambitious priorities were probably going to be achieved at a much slower rate than I had hoped, acknowledge that people in my life made me stronger, and most importantly, forgive myself for the many mistakes I made over the past three years. Only then was I able to truly move forward.